How To Clean A Catheter Bag Video

An overview of catheter drainage and support systems

Abstract

This article, the third in a six-part series on urinary catheters, provides an overview of drainage devices and catheter support systems. It also explains the procedure for emptying a catheter bag.

Citation: Yates A (2017) Urinary catheters 3: catheter drainage and support systems. Nursing Times [online]; 113: 3, 41-43.

Author:Ann Yates is director of continence services, Cardiff and Vale University Health Board.

- This article has been double-blind peer reviewed

- Scroll down to read the article or download a print-friendly PDF here (if the PDF fails to fully download please try again using a different browser)

- Click here to see other articles in this series

Introduction

Urinary catheterisation is associated with a number of complications including catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI), tissue damage, bypassing and blockage. The risk of complications means catheters should only be used after considering other continence management options, and should be removed as soon as clinically appropriate (Loveday et al, 2014).

During the insertion procedure tissue trauma and poor aseptic technique can lead to CAUTI; this risk continues for as long as the catheter is in place. Risk factors for CAUTI are outlined in Box 1. Appropriate catheter drainage and support devices, as well as hand hygiene and associated infection prevention strategies, can reduce the risk of CAUTI.

Box 1. CAUTI risk factors

The risk of catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI) is increased when:

- The connection between the drainage device and catheter is broken

- The drainage device's tap becomes contaminated when the bag is being emptied or comes into contact with the floor

- Reflux of urine from the bag into the bladder occurs because the bag is full or positioned above the level of the bladder

- There is poor hand hygiene before the catheter is handled by the patient or carer

- Patients have poor oral intake and/or level of personal hygiene while caring for their catheter

- The catheter is inadequately secured, causing trauma to the urethra and bladder neck

Catheterisation can have a profound effect on patients' lifestyle and sexual relationships (Prinjha and Chapple, 2013; Royal College of Nursing, 2012) so it is vital that patients are involved in the selection of drainage and support devices, and that their ability to manage these independently is assessed.

Selecting a drainage system

The selection of an appropriate drainage device depends on:

- The reason for, and likely duration of, catheterisation;

- Patient preference;

- Infection prevention issues (Dougherty and Lister, 2015).

There are a number of catheter bag types including:

- Two-litre bags – used for non-ambulatory patients and overnight drainage;

- Leg bags – can be worn under clothes, thereby encouraging mobility and rehabilitation as patients do not have to carry a bag attached to a catheter stand. Leg bags can also have a positive effect on patients' dignity as they are not visible to others (Dougherty and Lister, 2015);

- Urometer bags – used to closely monitor urinary output.

Principles that health professionals should bear in mind when managing drainage devices are highlighted in Box 2.

Box 2. Principles for managing drainage devices

- Catheters must be attached to an appropriate drainage device or catheter valve (see part 5 on catheter valves to be published in the May issue)

- The connection between the catheter and urinary drainage system must not be broken unless clinically indicated (Loveday et al, 2014)

- Catheter bags should be changed according to clinical need – for example, if the bag is discoloured, contains sediment, smells offensive or is damaged (Royal College of Nursing, 2012), or as instructed by manufacturers (Loveday et al, 2014), which is usually every seven days (RCN, 2012)

- Catheter specimens of urine should be obtained from a sampling port on the catheter drainage device according to local policy

- Bags should be positioned below the level of the bladder (Loveday et al, 2014); many are fitted with an anti-reflux valve

- Urinary drainage bags should not be allowed to fill beyond three-quarters (Loveday et al, 2014)

- When a 2L drainage bag is used, it should be attached to an appropriate stand and contact with the floor should be avoided (Loveday et al, 2014)

- A separate clean container should be used to empty bags, avoiding contact between tap and container (Loveday et al, 2014)

- Antiseptic or antimicrobial solutions should not be added to urinary drainage bags (Loveday et al, 2014)

- Catheters must be well supported to reduce traction-related problems such as bypassing of urine, and discomfort and soreness around the catheter

Leg drainage bags

Leg bags should be connected to the catheter to create a sterile closed-drainage system (Loveday et al, 2014), and changed in line with manufacturers' recommendations or when clinically indicated (Loveday et al, 2014). If the bag becomes disconnected from the catheter it should be replaced with a new one immediately.

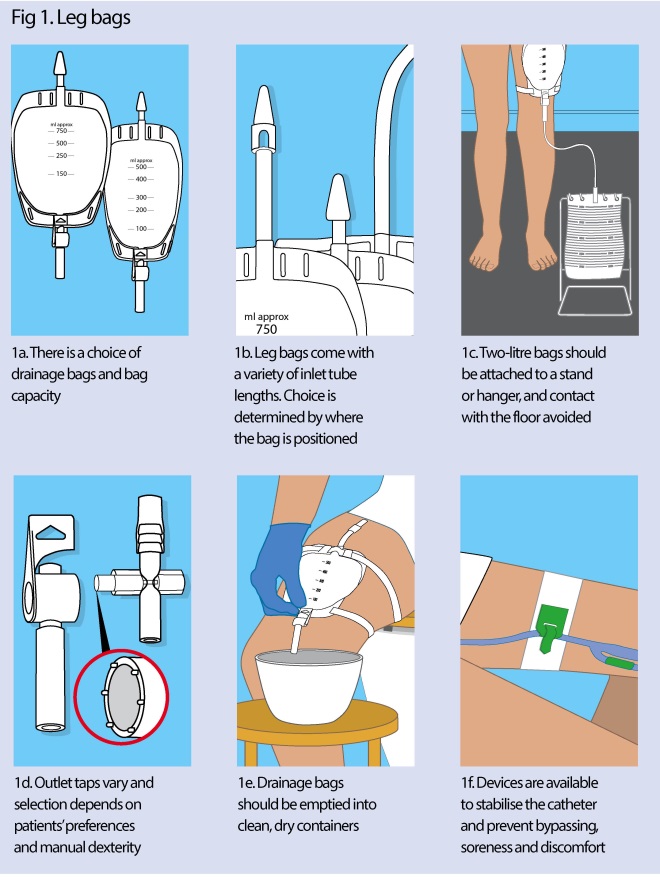

Leg bags come in a variety of sizes (Fig 1a) including:

- 350ml – a small capacity bag;

- 500ml – the most common choice for daily use;

- 750ml.

The capacity required can be determined by the patient's urine output.

Leg bags come with three lengths of tubing (Fig 1b):

- Direct inlet – attaches directly to the catheter;

- Short tube;

- Long tube.

Patients should be allowed to decide where they intend to wear their leg bag (thigh, knee or lower leg) as this will determine the length of the inlet tube used. This can be done via trial and error, and patients may wish to try a variety of products. It is important the leg bag is always positioned below the bladder to maintain urine flow.

Bags come in different shapes, including rectangles and ovals, and some have a fabric back to improve patient comfort when it is in contact with the skin (Dougherty and Lister, 2015).

Two-litre drainage bags

Two-litre capacity bags can be connected to the bottom of leg bags at night. The outlet tap on the leg bag is left open so the urine collects in the larger bag, which should be disposed of daily after use.

Bags should be supported on a stand or support hanger and should not be allowed to rest on the floor as this increases the risk of contamination and infection (Fig 1c, Loveday et al, 2014).

Two-litre bags can also be connected directly to a catheter and can be used post-operatively, if patients are confined to bed or if the use of a leg bag is not appropriate.

Outlet taps and bag emptying

There are a number of tap options available; if required, patients must have the manual dexterity to operate the mechanism at the outlet. The most common types are the lever tap and a 'push-across' type (Fig 1d).

The bag should be emptied regularly before it becomes too full and causes either damage to the urethra or reflux of urine into the bladder – this is normally when it is about three-quarters full. It is not advisable to open the tap to empty the bag more frequently as this can result in CAUTI.

Patients who are independent and able empty the catheter bag for themselves should be taught to:

- Wash their hands;

- Open the tap and empty the bag, either into the toilet or appropriate receptacle;

- Close the tap and wipe the outlet dry with a clean tissue or wipe to prevent urine drips;

- Wash their hands.

If a patient is unable to perform the task independently, carers should follow the procedure below.

Emptying a catheter bag

In an acute or institutional setting the procedure is as follows:

- Discuss the procedure with the patient.

- Screen the bed to ensure privacy and maintain dignity.

- Assemble the equipment including:

- Disposable gloves;

- Clean container for single patient use;

- Paper towels.

- Wash and dry your hands and put on the disposable gloves. This reduces the risk of infection.

- Clean the outlet port of the catheter bag according to local policy to reduce the risk of infection.

- Open the catheter bag port and drain the urine into a separate clean, dry container for each patient (Loveday et al, 2014) (Fig 1e). Do not touch the outlet tap with the side of the container as it could increase the risk of CAUTI.

- Once urine has ceased draining, close and clean the outlet tap, following local policy.

- Cover the container with a paper towel, and dispose of contents in sluice or toilet.

- Remove and dispose of your gloves according to local policy.

- Ensure the patient is comfortable.

- Wash and dry your hands.

- If required, record on the fluid balance chart the amount of urine that has been collected.

Supporting accessories

It is important that the catheter and bag are well supported to prevent damage to the urethra and bladder neck. There are a range of devices that help to prevent traction on the catheter. The catheter can be secured to the thigh using devices that have been specifically designed to prevent movement of the catheter and urethral traction, and can improve comfort and bladder drainage (Freeman, 2009) (Fig 1f).

The method used to secure the catheter should suit the patient's lifestyle and be simple to use. Devices are available on prescription and are now a vital part of good catheter management.

Leg bags are routinely supplied with a pair of latex/Velcro leg straps: one fits the top of the bag, the other fits the bottom. However, these can act as a tourniquet as there is no guidance on how much tension to apply. Care should be taken as they can restrict venous and lymphatic flow, increasing risk of deep vein thrombosis in patients with impaired circulation (Freeman, 2009).

An alternative is a sleeve that completely encases the leg bag and has a small opening for the tap, making it easy to access and empty (Fig 2). This method helps to distribute the weight of the bag more evenly so is useful for patients who have frail skin or if the straps dig or rub into the skin.

fig

Fig 2. Leg-bag sleeve

Everyday patient advice

Patients should be advised to:

- Wash their hands before and after handling their catheter;

- Bathe or shower daily to maintain meatal hygiene (Loveday et al, 2014);

- Drink at least eight cups of fluid a day and avoid caffeine where possible;

- Avoid constipation, as pressure from a full rectum can prevent urine drainage;

- Avoid kinking the catheter tubing so urine can drain freely;

- Empty the drainage system when it is three-quarters full;

- Keep a closed system of drainage.

Patients caring for their own catheter need to know what equipment they are using, how to order more and how to dispose of it safely. They also need to be able to recognise when they need specialist or medical advice – for example, if they experience urinary tract infection, bleeding, pain or bypassing – and who to contact for assistance (RCN, 2012).

Professional responsibilities

This procedure should be undertaken only after approved training, supervised practice and competency assessment, and carried out in accordance with local policies and protocols.

Freeman C (2009) Why more attention must be given to catheter fixation. Nursing Times; 105: 29, 35-36.

Dougherty L, Lister S (2015) The Royal Marsden Hospital Manual of Clinical Nursing Procedures. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Loveday HP et al (2014) epic3: national evidence-based guidelines for preventing healthcare-associated infections in NHS hospitals in England. Journal of Hospital Infection; 86: S1, S1–S70.

Prinjha S, Chapple A (2013) Living with an indwelling urinary catheter. Nursing Times; 109: 44, 12-14.

Royal College of Nursing (2012) Catheter Care: RCN Guidance for Nurses.

How To Clean A Catheter Bag Video

Source: https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/continence/urinary-catheters-3-catheter-drainage-and-support-systems-13-02-2017/

Posted by: penapayeads.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How To Clean A Catheter Bag Video"

Post a Comment